October 27, 1944 Friday

The descent from the high mountains was over. During this overcast late afternoon we were spread out in open ranks and walking toward a road visible at the end of the gentle slope. Suddenly the whole platoon was ordered to lie down along a rise, with weapons ready. Four of us were detailed as point men to go down close to the road.

Beside me was Ivan-Vrutky with his light machine gun. With him came as a helper one of the young, unarmed shepherd boys. The fourth was an older guy with a rifle. He was about fifty, heavy set, with grey whiskers. Our foursome moved ahead through a clump of thick bushes and lied down at the edge of a clearing. We were close to and slightly above an unpaved road. To our left and right the road disappeared from our view behind a bend. Beyond the road and a meadow, a narrow river burbled toward the northeast. Near the far bank of the river rose a steep, forested mountain. Turning back I could see the rest of our platoon up on the slope, about fifty meters behind us.

No matter how plainly I am trying to describe the events that followed, they sound improbable, even melodramatic.The four of us were lying on our stomachs, wordlessly watching the road. Our main group behind us was also quiet. Time passed. The sky looked grey, it was sometime after five o'clock. Suddenly a detachment of about twenty German soldiers came from around the bend to our right. They were marching in close-order formation. I did not see any of them wearing helmets. The soldiers started to sing a tune well known from broadcasts and newsreels. The four of us looked at each other and pressed closer to the ground, trying to disappear. I was stunned and scared. We were in our free hinterland, in SNP Uprising territory and did not expect to encounter enemy troops. All of a sudden our platoon started firing over our heads at the Germans. They immediately started to disperse and take cover. An Unteroffizier or sergeant remained standing in the middle of the road giving orders. His team began to shoot back in our direction and a few, hunched low, began to run toward the four of us.We started to shoot back and the firing from our main group, spread out at a safer distance, intensified. I did not notice any of the German soldiers falling down and some were getting closer. Outnumbered and with our position given away when our platoon fired the first shot, the four of us turned to run back toward the bushes in our rear.

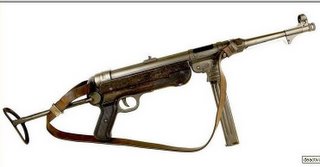

The first to reach the thicket were the shepherd boy and the older fellow. My namesake Ivan-Vrutky was firing bursts from his light machine gun and I was shooting with my rifle as two or three Germans came almost level with us. We too started to run toward the bushes. Everything was happenning very fast, there was no time to think, every move was controlled by instinct. Bullets were snapping and whistling in the air. I saw a few faces staring down at us from the hill where the rest of our platoon was positioned. Ivan-Vrutky was running hunched down a few paces ahead and to the right of me. Suddenly I saw sparks on the side of the weapon he was carrying and after a step or two he fell. I threw myself on the ground and looked at Ivan-Vrutky who did not move. The shooting stopped and as I lay at the base of an old willow tree I noticed that it was getting darker. I waited a while and then started to wiggle myself free of the rucksack and the rolled up blanket on my back; they hampered my movement. As I was starting to get up there came the familiar "prrrrr" noise of a Schmeisser submachine gun and woodchips started to fly from the trunk of the willow. I jumped up and turning around fired off my rifle in the direction of a German who was about twety-five meters away. If there were other soldiers nearby I did not notice them. Then came a powerful punch in my belly and I passed out.

I do not know how long I was out cold. I regained consciousness lying on my side, the rifle beside me. It was quiet and almost dark. I raised myself and looked down at my stomach where there sat a dull ache. I was staring at the signs of good shooting on the part of the enemy soldier and at the sign of a miracle or amazing good luck. The top left corner of my military belt buckle was dented in. The cartridge pouch beside the buckle was torn open. The five cartridges in the pouch, while still held by their clip, were distorted out of shape; all five have exploded and their bullets were expelled. The small handgrenade, still hanging from the torn pouch, had a dent in its top; a bullet from the Schmeisser must have grazed it. Apart from some soreness and being thoroughly shaken by what happened or could have happened to me, I did not get a scratch.

After the war, on 29 August 1945, there was in Banska Bystrica a celebration of the first anniversary of the SNP (Slovak National Uprising). Wearing a uniform borrowed for the occasion I met Janko Burian and other guys from our original platoon. I also received a big hug from one of the girls. They all had the same story to tell: They saw me go down and gave me up for dead.As I was looking around, listening and trying to get my 17-year old brain to function again. I heard my name being called by someone in the bushes. There was no sign of the Germans. In the bushes I found the young shepherd and the "old" guy, both unharmed. Ivan-Vrutky was lying on his back, his neck and bared chest covered in blood. He was moaning and wheezing, crying from pain; he seemed about to expire.

It was quiet and we could hear the river. We sensed that the rest of our platoon retreated into the mountains and we were on our own. We did not know the wherebouts of the soldiers and worried that Ivan-Vrutky's moaning will give away our hiding place. Bullets have struck his light machine gun and from there fragments hit his chest, causing the bleeding. The three of us sat there in the light drizzle with our wounded comrade and tried to keep him quiet. Finally the older fellow and I decided to have another look at those wounds, though we could barely see anything in the gloom. There were four or five surface wounds in the chest with small pieces of metal sticking out. We managed to pick them out with our bare and dirty fingers, scared because of Ivan-Vrutky's louder moaning and his babbling that he is going to die. He did not. The "old" guy pulled from his knapsack a small box from which he sprayed powder on my wounded friend's chest. He then produced a roll of dark, gauze-like material with which we bandaged the already quieter patient.

We started to discuss in whispers our next move. At this point the young shepherd boy said that he was returning to his village and left us. Ivan-Vrutky seemed to have fully recovered by now and started to move about. The three of us agreed that we will cross the road and the river, go into the hills on the other side and will try to make our way toward Bystrica. We had no idea how long it will take, we did not know where we were. We were without a map or compass. We have forgotten that that we had no food.

The night of October 27-28, 1944

________________________________

The machine gun and our rucksacks were left where they have earlier fallen. We kept our heavy coats and knapsacks. Between the three of us we had two rifles and a few handgrenades. There was a partial moon in the sky which made the road appear bright, anyone crossing it would have been clearly visible. We waited until midnight then started to crawl on our stomachs through the wet grass and mud. Occasionally we lifted ourselves to move faster on our hands and feet. We stopped frequently to look and listen, the events of the earlier hours made as very cautious. It took us over two hours to reach the ditch on the near side of the road. To avoid showing up as silhouettes and recognizable targets against the surface of the road, we rolled and slithered across the road to the meadow on the other side. We then rushed to the river and waded in. It was cold on this late October night. We slowly crossed holding on to each other with the two outstretched rifles. Our luck held,the water at its deepest point only reached to our thighs. On the other shore we quickly moved into the bushes at the base of the mountain. There we rested and tried to squeeze the water from our clothes and long coats.

Without waiting for daybreak, the three of us started on a slow and long climb that took us most of the day. No water, no food. We passed through thickly forested stretches. The occasional clearings were covered in mist and fog. We did not know where we were. I did not know that worse days waited ahead.